Learn more about the history and cultural significance of Wagashi, Japanese confectioneries. From local specialties, seasonal varieties to the everyday desserts, you’d gain a much deeper appreciation as you enjoy the sweets year round.

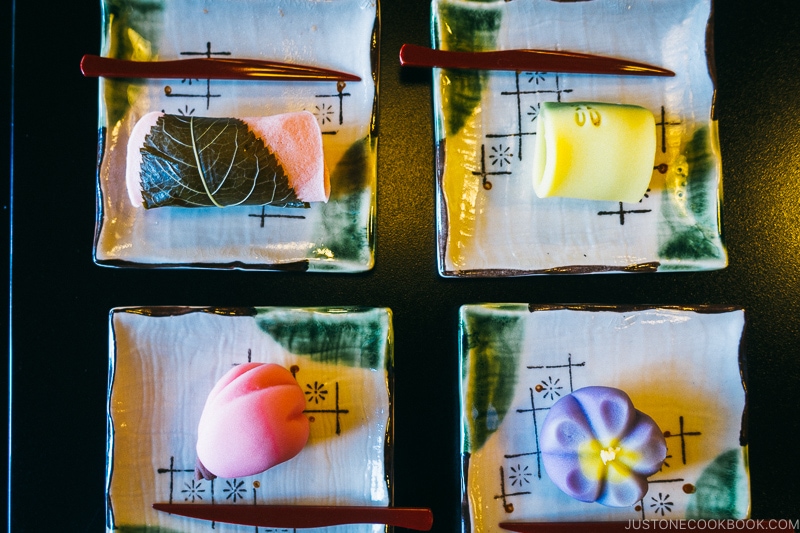

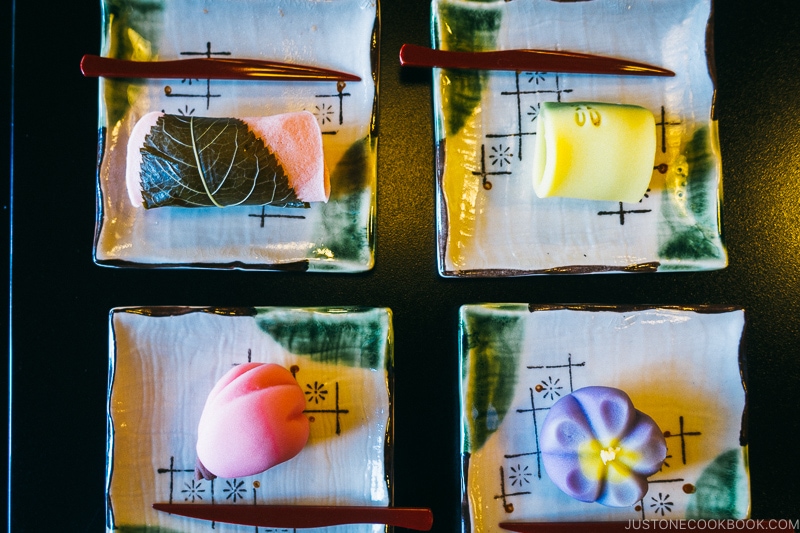

You may have seen beautiful pieces of sweets displayed at a confectionery section of Japanese department stores or supermarkets. Some resemble motifs from nature such as flowers, leaves or fruits. It may be made of bean paste, mochi or jelly-like substance. They look more like miniature pieces of art. Are they really edible, you wonder. And does it taste as good as it looks?!

Called Wagashi (和菓子), these Japanese confectioneries carries a rich history entwined with Japanese culture. There’s more than meets the eye (and stomach)!

In this two-part series on Wagashi, let’s first explore its cultural and historical significance to the Japanese.

What is Wagashi?

The term Wagashi encompasses all Japanese desserts, from the tea ceremony delicacies to the everyday desserts. You may have seen them featured in Japanese movies or dramas, such as Dango (団子 skewered mochi balls), Dorayaki (どら焼き mini pancakes sandwiching a sweet filling), or Sakura Mochi (桜餅 cherry blossom pink mochi with red bean paste inside).

Compared to European desserts, which is characterized by the abundance of butter and eggs, traditional Wagashi calls for minimal oil, spices, and dairy products. The main ingredients are grains such as wheat or rice, starches from beans such as red beans and soybeans, and sugar.

Wagashi comes in all sorts of shapes and sizes, but most are small enough to be eaten within two or three bites.

Wagashi and Japanese Tea Ceremony

How does wagashi pertain to Japanese tea ceremony? In a Japanese tea ceremony (茶道) context, Wagashi is served to accompany and complement the bitter taste of Matcha (抹茶 Japanese green tea made from powdered young green tea leaves). Wagashi is always consumed before the Matcha is served, and never together.

The deep appreciation of the seasons is reflected in the aesthetics of Wagashi. For example, you may see plum blossoms and cherry blossoms motifs in the spring, young green bamboo leaves and fireworks in the summer, autumn foliage, and the harvest moon in the fall, and snow in the winter.

However, Wagashi isn’t limited to the tea ceremony scene; it can be eaten like any other dessert for your midday, afternoon tea or a post-meal dessert. You don’t need to pull out your matcha whisk and bowl; you can pair it with other types of green tea, non-green teas, coffee, or whatever you prefer!

To understand the world of Wagashi, let’s first understand its history.

The History of Wagashi

As stated above, the history of Wagashi and Japanese tea ceremony (茶道) are intricately linked. It’s impossible to separate the two when approaching their respective origins.

Ancient artifacts have shown that the Japanese have been craving for sweetness, back to the Yayoi period (300 B.C.-300 A.C.) where the people ate the natural sweetness found in fruits and nuts.

Trade with the Sui and Tang Dynasties during the Asuka period (538-710) brought back various types of Chinese confectioneries. One called Kara-kudamono (唐果物), a type of deep fried mochi made from rice, wheat, and soybeans, is said to be the origins of Wagashi. However, these delicacies were served at the Imperial Court and religious deities, and not circulated among the commoners. Sugar was a luxury import good that was rare, and its primary use was for medicine.

Different types of Kara-Kudamon (Source)

Tea was introduced from China around the Kamakura period (1185-1333) and the habit of drinking tea by Zen monks is established around this time. As part of the ritual, a simple meal called Tenshin (点心 dim sum) and snacks were served. As sugar was still not easily available, the sweet substance was made of the sap of grape ivy (甘葛). The meal served with the tea ceremony (茶席) becomes more elaborate during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), as Zen becomes connected with the upper Samurai class.

The availability of sugar becomes more widespread due to the Portuguese merchants, who introduced new culture and cuisine to the Japanese. The Japanese aristocracy was hungry for Portuguese delicacies, and they adapted it into what was called Nanbangshi (南蛮菓子). These exotic sugar and egg loaded desserts such as Castella (カステラ) and Kompeito (金平糖) (from the Portuguese confectionery ‘Comfit’) were only for the nobility.

The Burgeoning of Wagashi in Japan

The demand and production of Wagashi exploded during the Edo period (1603-1867), due to the widespread commercialization throughout the country and significant improvement in agricultural productivity. Sugarcane from Okinawa and Shikoku, and processed white sugar became available in the capital (Edo) and Kyoto. This spurred the development of new Wagashi specialty stores. In parallel, the culture of tea ceremony also flourished, where serving delicious sweets became one of the most important aspects of the ceremony.

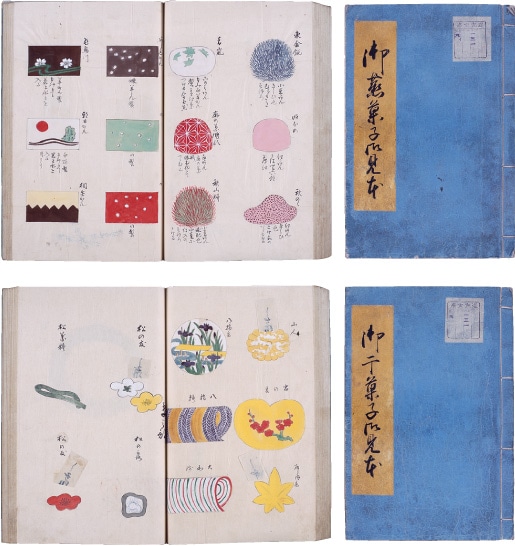

Edo period booklets depicting various types of Wagashi (Source).

With the fierce competition among Wagashi confectioners to meet their hungry customers’ demand, different styles with intricate designs became popular. Kyoto-styled Wagashi called Kyo-gashi (京菓子) was the beautiful pieces of edible art for tea ceremony, whereas the middle-class Edo (Tokyo) craved for the more simple and approachable Jyo-gashi (上菓子).

The term Wagashi was born during the Meiji era (1868-1912), during the era of rapid modernization and westernization. Like how Washoku (和食) was a term to distinguish from foreign food cultures, Wagashi – wa (和 Japanese) and kashi/gashi (菓子 sweets) – was born.

Ready for More?

The traditions of Wagashi still lives on to the present day. If you’re visiting Japan, stop by a tea shop to sample a few pieces with a cup of tea. You can find shops and stores serving up wagashi in major tourist areas like Kyoto and Kanazawa and big department stores. If you’re in a small town, do check out the local varieties. Some places offer classes on how to whisk a cup of matcha!

The next post will cover more on the different varieties and categories of Wagashi. Thank you for reading until the end and stay tuned for Part 2!

Sources:

- The Essence of Japanese Cuisine: An Essay on Food and Culture (Source)

- The Japan Wagashi Association (Source)

- National Diet Library, Japan (Source)

- Wagashi: Japanese traditional sweets or works of art? (Source)

- 全国菓子工業組合連合会(全菓連) (Source)

Kayoko happily grew up in the urban jungle of Tokyo and in the middle of nowhere East Coast, U.S. After a brief stint as a gelato scooper and slightly longer employment at an IT company, she decided to drop her cushy job to enroll in culinary school. Kayoko resides in Tokyo with her husband, a penguin pillow, and many half-dead plants. More from Kayoko →